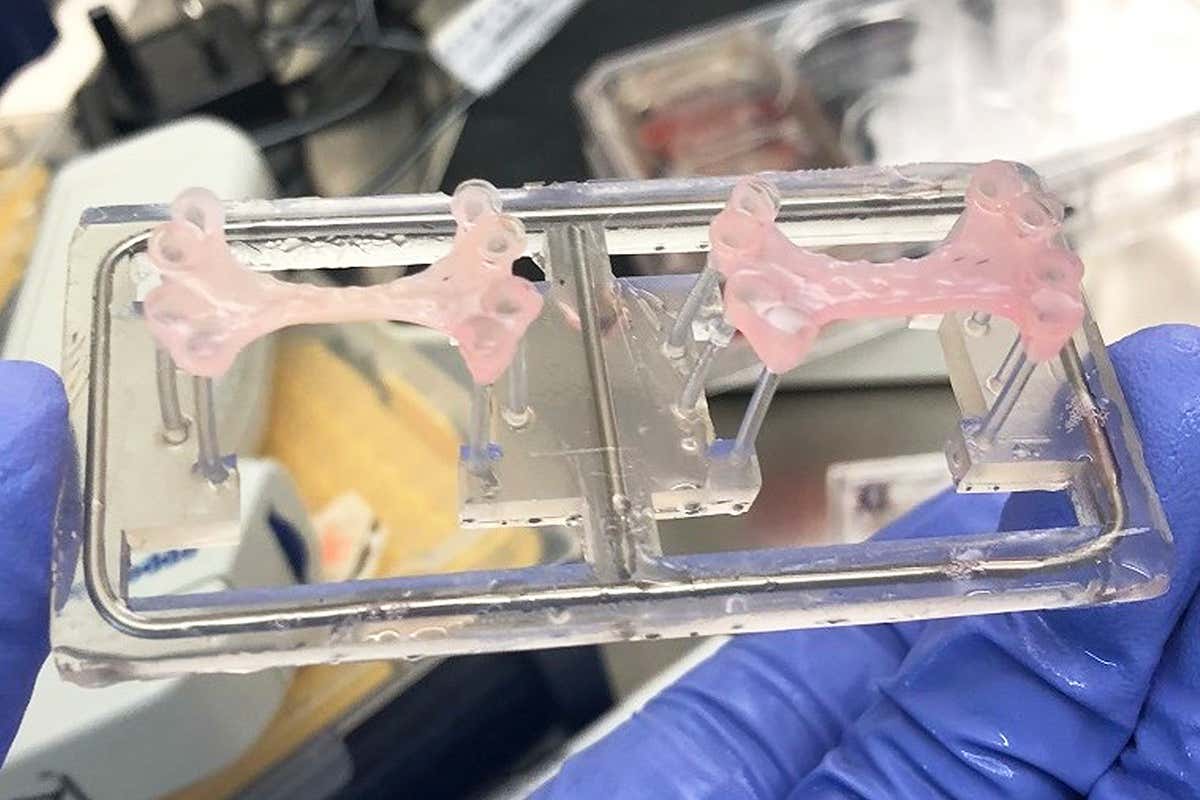

Patches could help repair damaged hearts. Credit: Imperial College London/Sian Harding[/caption]

Using stem cells to treat weakened heart muscle isn’t a new concept. But many existing methods injected stem cells directly into damaged tissue, and without a ‘scaffold’ to hold them in place, the cells would clear out of the heart before achieving significant tissue repair.

The team tested the patches in rabbits, finding that four weeks after implanting a patch, the hearts' left ventricles (the chamber that pumps blood to the body through the aorta) recovered without developing abnormal heart rhythms. They also found that blood vessels from recipient hearts grew into the patches and helped nourish them, a crucial step for integration. The patches started to beat spontaneously after just three days, and within one month started to mimic mature heart tissue.

Patches could help repair damaged hearts. Credit: Imperial College London/Sian Harding[/caption]

Using stem cells to treat weakened heart muscle isn’t a new concept. But many existing methods injected stem cells directly into damaged tissue, and without a ‘scaffold’ to hold them in place, the cells would clear out of the heart before achieving significant tissue repair.

The team tested the patches in rabbits, finding that four weeks after implanting a patch, the hearts' left ventricles (the chamber that pumps blood to the body through the aorta) recovered without developing abnormal heart rhythms. They also found that blood vessels from recipient hearts grew into the patches and helped nourish them, a crucial step for integration. The patches started to beat spontaneously after just three days, and within one month started to mimic mature heart tissue.

The next step is to test the safety of the patches through clinical trials, then attempt to use them to repair human hearts.

"One day, we hope to add heart patches to the treatments that doctors can routinely offer people after a heart attack,” said Dr. Richard Jabbour, who carried out the research. “We could prescribe one of these patches alongside medicines for someone with heart failure, which you could take from a shelf and implant straight into a person."

Professor Metin Avkiran, associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation, which funded the research, added “This is a prime example of world-leading research that has the potential to mend broken hearts and transform lives around the globe. If clinical trials can show the benefits of these heart patches in people after a heart attack, it would be a great leap forward for regenerative medicine.”

Image Credit: Sian Harding, Imperial College London

This article originally appeared on Singularity Hub, a publication of Singularity University.